Designing stationary lithium-ion storage systems correctly: Requirements, chemistry selection, system design & safety – Large-scale systems with Li-ion batteries put to the test

Why stationary battery storage systems are different and why service life, cycle profile and architecture are more important for buildings & grids than pure energy densities

Stationary Li-ion storage systems are not designed according to the same criteria as traction batteries. While mass and volume efficiency dominate in vehicles, safety, efficiency, service life (over 10 or 20 years) and a load-dependent cycle profile – from many short, shallow cycles for grid stabilization to deep cycles lasting several hours for PV self-consumption and load shifting – are what count most in the grid and building context. It is precisely this range that requires cells that are specifically optimized for the respective operating strategy.

Applications & load profiles at a glance

Stationary applications range from UPS/emergency lighting, telecom/IT and power plant backup to PV home storage, grid support/primary control power and arbitrage. In practice, this means

- Short-term power (seconds to minutes) for grid stabilization/UPS,

- Multi-hour energy shift (e.g. PV generation at midday → consumption in the evening),

- Decentralized home storage systems up to ≈ 100 kWh and central systems from ≈ 1 MWh.

For many applications: safety first, especially when installed in buildings; target service life ≈ 20 years (PV typically ~8,000 full cycles over the service life). Lithium systems also impress with > 95 % round-trip efficiency and low self-discharge.

Lessons learned from Automotive – but prioritized differently

Cell development in recent years has been strongly driven by the automotive industry: today, large-format cells ≈ 10-400 Ah are available in high-power (HEV) and high-energy (BEV) versions. These formats are used in stationary applications – but

Technical basis: cell and system requirements

For grid stabilization, cells with high power acceptance/output and flat DoD (Depth of Discharge) are ideal; for PV storage, high usable energy and low DoD with maximum service life are required. This only makes economic sense if several thousand cycles and over 10 (or even 20) years of operation are realistically achievable – which is determined by the cell chemistry, the operating window (U/I/T) and the thermal conditions.

Chemistry decisions: NMC vs. LFP – and why LTO/LFP scores stationary

NMC (e.g. LiNi₁/₃Mn₁/₃Co₁/₃O₂) offers high reversible capacities (≈ 200 Ah/kg) and is widely used in vehicles. LFP (LiFePO₄) provides a very robust, thermally stable cathode (up to ~250°C without decomposition-related runaway) at ~3.2 V cell voltage and ~155-170Ah/kg – predestined for safety-critical environments. The combination of LTO anode + LFP cathode is particularly interesting for extreme cycle life: lower cell voltage, but very low degradation; ~20,000 cycles without significant capacity loss were demonstrated in tests (for comparison: common Li-ion often ≤ ~4,000 cycles).

Brief overview:

- Safety and durability-critical applications (buildings, hospitals, data centers): Prefer LFP or LTO/LFP.

- Performance services (short, flat cycles): Chemistry with high rate capability and low resistance increase under cyclic load.

- PV storage (lower cycles over many years): LFP or LTO/LFP for calendar stability and cycle stability.

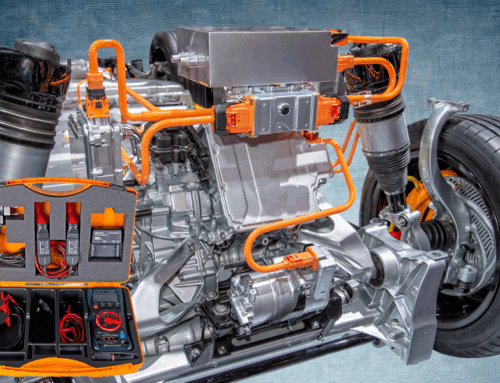

System level: BMS, thermal, connections, housing

It is well known that the cell is only one basic component of the battery. The overall system design (BMS/monitoring, cooling/heating, connection technology, housing/fire protection) determines performance, losses, service life and safety. Proper coordination of the components minimizes parasitic resistances and equalizing currents, keeps temperature stratification low and reduces ageing. BMS functions (SoC/SoH/SoP/SoF estimation, cell balancing, limit value and error handling) are essential – especially for large strings and modular racks.

Thermal management: In stationary applications, spatial freedom allows for more generous cooling concepts than in vehicles. The aim is not minimum weight, but stable temperature windows and homogeneous distribution in order to avoid imbalance and local sources of ageing.

Operating strategies that ensure a long service life

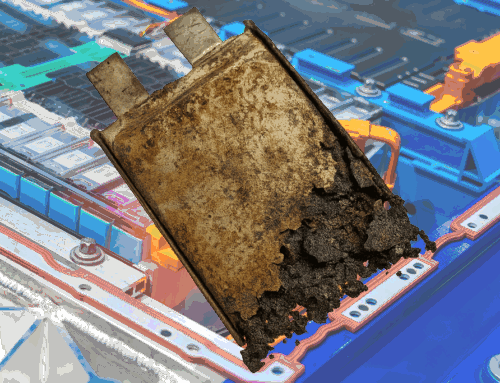

Service life is characterized by cycle and calendar ageing. In addition to material aspects, stationary factors have a particular effect:

- Operating window: moderate DoD, SoC average and temperature reduce SEI growth and resistance increase.

- Rates: appropriate C-rates (charge/discharge) avoid lithium plating and mechanical particle degradation.

- Strategies per application: Grid services (many short cycles) vs. PV (daily multi-hour cycles). The target value remains long-term stability over 10 or even 20 years.

Example PV: One cycle per day adds up to ~7 000-8 000 cycles over 20 years – a classic use case for LFP or LTO/LFP.

Efficiency & self-discharge – hidden yield drivers

Stationary efficiency counts directly: every percentage point of round-trip efficiency increases the economic benefit over the lifetime. Li-ion storage systems reach > 95 %, which makes them particularly attractive for arbitrage, PV self-consumption and load management; the low self-discharge supports longer holding times.

Safety: thinking chemistry, architecture and operation together

Safety results from the choice of materials (e.g. thermally robust cathodes), cell/module packaging (fire load, venting path, separation distances), electrics (creepage/clearance distances, protective conductor concept), function (BMS limits, fault management) and operation (temperature, SoC window). In stationary systems – often in buildings – the focus on safety is particularly high. LFP reduces the risk potential due to higher decomposition temperatures; appropriate protective measures and thermal concepts must be consistently designed for LCO/NMC.

Briefly on the testing and standards environment: Stationary systems are functionally monitored (voltage/temperature/current, insulation monitoring, fault reactions) and evaluated in fire protection/installation for specific applications. In buildings, safety takes priority – from installation location and ventilation to emergency handling.

Note (qualification/voltage levels): Handling battery systems below and above 60 V (or 120 V) requires different technical qualifications and safety measures. In practice, planning, installation, commissioning and service are regulated according to the voltage level and the place of use – only mentioned here for the sake of completeness.

Brief comparison with road vehicles

- Energy vs. power focus: vehicle batteries balance energy density and power density (HEV ↔ BEV); stationary batteries are optimized for specific applications (shallow vs. deep cycles).

- Service life target: Vehicle typ. ~8-15 years per use; stationary over 10-20 years with clearly defined cycle programs.

- Installation space & mass: In buildings, safety/service-friendliness counts more than kg/kWh; redundancy and modularity are key design features.

Architectural examples: Home storage to large-scale storage

Home/commercial (≤ 120 kWh): PV self-consumption, peak load capping, V2H concepts; AC or DC coupling per system topology. Large-scale storage (≥ 1 MWh): Grid support, control power, generation smoothing for wind/PV; electrochemical storage systems score points with location independence and scalable installation.

🎓Conclusionfor development & operation

Anyone specifying stationary Li-ion storage systems should think in terms of the load case: Which services? Which cycles? What service life and safety targets? This results in cell chemistry (often LFP, possibly LTO/LFP), operating window (SoC/DoD/T), thermal and BMS strategy as well as a system architecture that takes maintenance, fire protection and scaling into account. If this chain is consistently closed, Li-ion storage systems reliably deliver grid-supporting power over 10-20 years – from PV self-consumption optimization to control power.

Key points to take away and FAQ

- Requirement first: Short flat cycles ↔ low overtime cycles; select cell/system from this.

- Choose chemistry consciously: LFP for thermal robustness; LTO/LFP for extreme cycles.

- System makes the difference: BMS, thermal management, connections, housing → service life & safety.

- Efficiency counts: > 95% round-trip efficiency increases profitability.

1. why do stationary lithium-ion storage systems differ fundamentally from traction batteries in vehicles?

Stationary Li-ion storage systems are not optimized for energy density or weight, but for safety, service life and efficiency. While every kilogram counts in vehicles, cycle stability over 10-20 years, thermal stability and the cycle profile are decisive for stationary systems. This is why cell chemistries such as LFP (lithium iron phosphate) or LTO/LFP combinations are preferred, which are particularly suitable for buildings, grid applications and PV storage.

2. which cell chemistry is best suited for stationary battery storage in industrial applications?

LFP (LiFePO4) is usually recommended for stationary applications due to its high thermal safety, long service life and low fire risk. In particularly long-lasting systems, a combination of LTO anode and LFP cathode can enable over 20,000 cycles – ideal for PV systems, data centers or power plant backups.

NMC (nickel-manganese-cobalt) cells are preferred in vehicles, but are only suitable for stationary systems to a limited extent due to their lower thermal stability.

3. what safety requirements apply to stationary Li-ion storage systems in buildings and industrial facilities?

Safety is the top priority in buildings. Important factors are:

Thermally stable cell chemistry (e.g. LFP instead of NMC)

Fire protection-compliant housing design and ventilation systems

Insulation and fault monitoring via the BMS (Battery Management System)

Homogeneous temperature distribution to prevent local overheating

Training in an industrial environment teaches the requirements of standards, safety guidelines and practical behavior in the event of emergencies in order to ensure safe and standard-compliant operation.

4. how is the service life of stationary lithium-ion battery systems optimized?

The service life depends largely on the operating strategy and system design. Important influencing factors are:

Limited DoD (Depth of Discharge) to reduce ageing

Stable temperature control through targeted thermal management

Adapted charge/discharge rates (C-rates) to avoid lithium plating

Efficient BMS control for balancing and status monitoring

An optimally designed system achieves over 8,000 full cycles and an operating time of 10 to 20 years, which is economically decisive for PV and grid storage projects in particular.

5. what further education or training is required for handling stationary battery storage systems?

Professional handling of stationary battery systems – especially above 60 V DC – requires an electrical engineering qualification. Training courses are available:

Basics of battery technology and competence levels

Safety and standard requirements in accordance with DGUV, ArbSchG, ProdSichG and VDE/IEC

Practical knowledge of installation, commissioning and maintenance

Companies in the industry benefit from certified training programs that qualify and legally secure their specialists for the planning, installation and operation of stationary energy storage systems.

For us, the topic of batteries is definitely a standard part of every high-quality (ev) high voltage training course.

PS: Our recommendation: Our free(REALLY free, even WITHOUT having to provide an email address!) paper “6 things you need to know in advance about the high-voltage qualification of your employees” is available here (click).

Leave A Comment