Why materials determine performance, safety and costs

The performance of a lithium-ion cell stands and falls with its material combinations – from the active cathode and anode to the electrolyte and separator through to the collectors and binders. These components determine the voltage level, energy density, charging capacity, service life and safety behavior – and therefore also the process window and costs in battery production.

Cathodes: levers for voltage, energy density and risk

Coating oxides (LCO/NMC/NCA): capacity through nickel, cobalt down

Current development directions focus on low-cobalt mixed oxides and higher nickel contents to reduce costs and increase capacity; high Ni contents can enable specific capacities of up to ~190 mAh g-¹ (for comparison: established NMC variants ~160 mAh g-¹).

Spinelle (LMO, high voltage spinelle): Powerful, but electrolyte limited

LMO spinels deliver very high discharge currents (> 5 C), but are limited by a narrow voltage window during high-current charging. Nanostructuring improves the high-current capability, but usually requires coatings because Mn³⁺ solubility on large surfaces is critical.

(ev) high voltage spinels such as Li₁₋ₓ(Ni₀․₅Mn₁․₅)O₄ operate around ~4.7 V; other spinels range up to ~5.1 V, depending on the metal. The biggest hurdle is the oxidation stability of the electrolyte, which today is typically only stable up to ~4.3 V.

Phosphates (LFP/LMP): Thermally robust, electrically too tough – specifically compensated

LFP crystallizes in the olivine type; lithium diffuses one-dimensionally along [010] – important for the rate behavior.

The low electronic conductivity is addressed by nanostructuring and high-quality carbon coatings; high utilization rates (up to ~97 % of the theoretical capacity) and good high-current behavior can thus be achieved.

A decisive safety advantage: polyanionic phosphates do not release oxygen under load; LFP exhibits excellent thermal stability and broad electrolyte compatibility.

Manganese-containing olivines (LMP) increase the voltage (~4.1 V), but require even smaller particles (< 80 nm) due to low conductivity; 5 V olivines with Co/Ni currently fail due to electrolyte stability above ~4.3 V.

Implication for the selection:

- Maximum safety/robustness → LFP.

- Very high power → LMO (coated if necessary) or HV (ev) spinel – but note the electrolyte.

- High energy density → Ni-rich layer oxides.

Anodes: From graphite to alloy – and why zero SEI can be a game changer

Graphite: industry standard with clear physics

Non-solvated Li intercalates in graphite at 0-0.25 V (against Li/Li⁺) in clearly defined steps; the theoretical reversible capacity is 372 mAh g-¹ – practically achievable in high-quality graphites under low currents. A first cycle loss occurs due to SEI formation.

The optimized particle morphology (rounding, amorphous C-coating) is aimed at low surface area and stable SEI; high-quality synthetic graphites are produced via high-temperature graphitization.

Amorphous/hard carbons: high capacity with very slow charging

Additional capacity comes from Li adsorption in nanoporosity; industrially relevant is usually only the intercalation part. Characterized by high hysteresis and high first-cycle loss, but often better high-current absorption than graphite.

Silicon and tin: capacity wonders with volume work

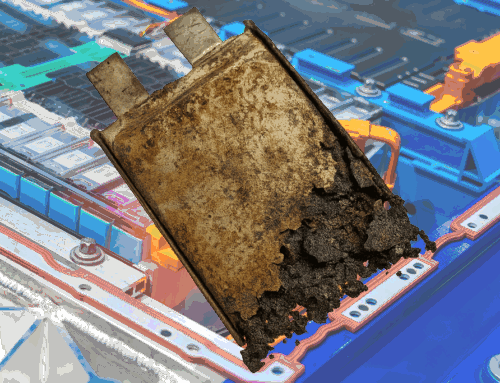

Alloy anodes (Si, Sn) deliver very high theoretical capacities (e.g. Li₄․₄Sn ~ 993 mAh g-¹), but suffer from massive volume changes, amorphize and thus lose cycling stability. Countermeasures are nanoparticle design, C-composites and reactive binders – at the expense of specific capacity.

LTO (Li₄Ti₅O₁₂): “zero strain” for safety and service life

Lithium titanate intercalates at ~1.55 V, reaches ~160 mAh g-¹, shows virtually no volume change, requires no SEI and has very low impedance – resulting in excellent cyclability and high safety.

Implication:

- High energy density → graphite (possibly Si content).

- Highest security/lifetime → LTO.

- High charging power/low temp → use hard C fractions in a targeted manner.

Electrolyte & conducting salt: More than “just” ion transport

Requirements profile and modular system

Modern electrolytes are high-purity multi-component systems; requirements include high conductivity from -40 °C to +80 °C, high cycle stability and broad chemical compatibility. There is no such thing as “the” perfect electrolyte – conflicting objectives remain.

The modular system includes solvents, conductive salts and additives.

Solvent: EC as SEI anchor, PC with graphite problematic

Combinations of cyclic (EC/PC) and linear carbonates (DMC/DEC/EMC) balance permittivity and viscosity. EC is almost always added (20-50 %) because it produces a dense, electronically passive and Li⁺-conductive SEI. PC, on the other hand, does not form a suitable SEI on graphite; it co-intercalates and destroys the graphite structure.

Conductive salts: LiPF₆ as the industry standard

LiPF₆ dominates commercial electrolytes due to a unique combination of properties – despite accepted disadvantages – and ensures high Li⁺ mobility in common carbonate systems.

Additives: The “master spit” for service life and (ev) high voltage

SEI formers such as vinylene carbonate (VC) – standard in many cells – significantly improve cycle stability by preferentially reducing them and creating a thin, elastic film. FEC/VEC and SEI-active salts such as LiBOB are alternatives or co-additives.

LiBOB, for example, reduces Mn leaching from LMO cathodes by an order of magnitude even at low additions and specifically influences the SEI structure.

At the positive electrode (relevant for HV technology), CEI passivation via additive oxidation is key, as true thermodynamic stability at ~5 V cannot be achieved.

Separator: The invisible seat belt

Function, parameters and tests

Separators prevent electrode contact, but allow ion transport; porous, electrolyte-impregnated surface structures with typ. ~40 % porosity. Consumer cells use

Dry vs. wet diaphragm; shutdown concepts

Polyolefin membranes are manufactured as dry or wet membranes. Wet processes (often UHMW-PE + wax, bidirectional stretching, extraction) provide lower anisotropy; surface hydrophilization improves wetting and shortens cell filling time.

Multilayer PP/PE/PP separators realize “shutdown”: PE melts earlier (~130-135 °C) and closes pores, PP (~165 °C) supports mechanically – but this only works with a slow temperature increase; overall, the melt-down of PP limits the upper safety threshold (~160 °C).

Collectors, binders & process: the underestimated third

Current arresters: aluminum vs. copper – for good reason

Active compounds are coated on metal foils: cathodic mostly Al (typically 20-25 µm), anodic Cu (8-18 µm). Al cannot be used at negative potential (Li-Al alloys), therefore Cu.

Binder, carbon black and solvent: fine-tuning between energy and performance

PVDF is the classic binder (usually processed in NMP); water-based binders are becoming increasingly important, especially on the anode (explosion protection, exhaust gas purification not applicable). Conductive carbon black (~1-5 %) and binder (~2-8 %) are trade-off levers: energy cells minimize inactivation, power cells prioritize contact and conductivity.

Process steps with influence on quality

Mixing, dispersing, coating, drying, cutting, calendering – the specific energy input during dispersing and the homogeneity of the slurry are key variables relevant to scaling.

Cell formats and housings: material consequences in the system

Hard case cells use aluminum or stainless steel housings; pouch cells use multilayer composite films (e.g. PA/Al/PP). Internal structures are round wraps, flat wraps or stacked “stacks”. The choice of format influences the requirements for mechanics, filling and wetting.

Practical takeaways for development & production

- Define target parameters: Prioritize energy density, performance, safety, temperature window and costs early on – material selection follows from this. (Example: LFP for robustness; Ni-rich layer oxides for range; HV (ev) spinel only with adapted additive electrolyte).

- Actively design SEI/CEI: Use additives (VC/FEC, LiBOB) specifically for service life, (ev) high voltage passivation and Mn stabilization.

- Separator suitable for the format: Match thickness/porosity and membrane technology (dry/wet) to cell format and safety strategy (shutdown).

- Process control: Slurry homogeneity, calender window and drying are just as critical to performance as the active material.

Conclusion

Material selection is system design: cathode and anode set voltage and capacity, electrolyte and additives enable service life and (ev) high voltage, separator and housing secure and structure – and collectors/binders and the process provide the often underestimated percentage points. If you think about these levers together, you can reliably bring cells into the desired window of energy density, performance and safety – and at the same time create robust, scalable production windows. The material details are more likely to be found in battery technology training, and are also mentioned in the (ev) high voltage training courses required for this. PS: Our recommendation: Our free(REALLY free, even WITHOUT having to provide an email address!) paper “6 things you need to know about the high-voltage qualification of your employees in advance” is available here (click).

Leave A Comment